Aiming for Atoms: The Art of Making Chips Smaller

In the world of estimator chips, bigger numbers are oftentimes meliorate. More cores, higher GHz, greater FLOPs, all desired by engineers and users alike. But at that place is i measure in semiconductors that's hot right now, and the smaller, the better. Enter semiconductor manufacturing and the applied science node (a.k.a. the process node).

Simply just exactly what is it, and why is it so important? Why is information technology measured in nanometers, and why are we going all Sesame Street and bringing this article to you with the numbers 10, 7 and 5?

Let'due south take a journeying into the world of procedure nodes...

But earlier we delve into things, you volition gain a amend understanding of things if you go through our CPU architecture serial. In part one, we cover the fundamentals of how processors piece of work and in part two, we examine how engineers plan and design chips.

The cardinal section relevant to this article is the explanation of how computer fries are physically put together. You'll want to read the section on photolithography advisedly if you lot desire an in-depth understanding of the manufacturing process, while in this feature we'll focus more than on this bespeak that was briefly touched upon:

One of the biggest marketing terms associated with chip fabrication is the feature size.

In the flake industry, the feature size relates to something called the procedure node. Every bit we mentioned in How CPUs are Designed, Office iii, this is a fairly loose term, as unlike manufacturers use the phrase to describe different aspects of the scrap itself, only not so long ago information technology referred to the smallest sized gap between two sections of a transistor.

Today it's more of a marketing term and not very useful for comparing production methods. That said, the transistor is a disquisitional feature of any processor, as groups of them perform all of the number crunching and data storage done within the chip, and a smaller process node from the same manufacturer is a very much desired thing. The obvious question to ask here is why?

Nothing in the globe of processors happens instantly and neither does it have identify without requiring a source of electrical energy. Bigger components take longer to modify their state, signals accept longer to travel, and more energy is needed to movement electricity about the processor. Without trying to sound obtuse, bigger components also take upward more physical space, so the chips themselves are larger.

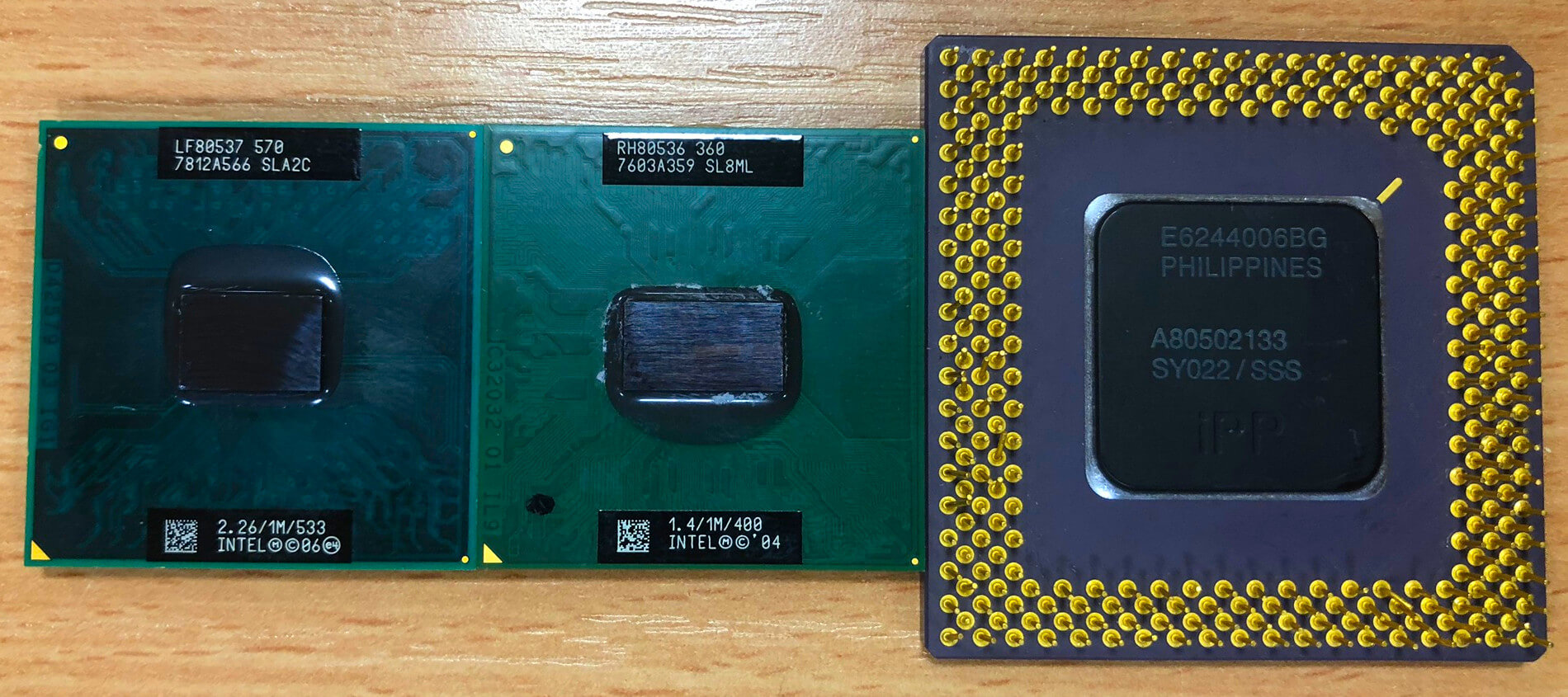

In the above prototype, we're looking at three erstwhile Intel CPUs. Starting from the left, we have a 2006 Celeron, a 2004 Pentium M, and a really old Pentium from 1995. They have a process node of 65, ninety and 350 nm respectively. In other words, the critical parts in the 24 year quondam design are more than 5 times bigger than the 13 yr quondam i. Some other of import difference is that the newer chip has effectually 290 meg transistors packed inside, whereas the original Pentium has simply over 3 one thousand thousand; almost a hundreds times fewer.

Although the reduction in process node is only part of the reason why the more contempo blueprint is physically smaller and has more transistors, it does play a pregnant role in Intel beingness able to offer this.

Just here's the existent kicker: that Celeron only produces around thirty W of heat, compared to the Pentium's 12 Due west. This estrus comes from the fact that as electricity is pushed around the circuits in the flake, energy is lost due through various processes and the vast majority of it is released as heat. Yes, 30 is a bigger number than 12, simply don't forget that the flake has about 100 times more transistors.

So if the benefits of having a smaller procedure node results in smaller chips, touting more transistors that can switch faster -- which gives us more calculations per second -- and less energy lost every bit heat, it does beg some other question: why isn't every chip in the world using the smallest possible process node?

Allow there be light!

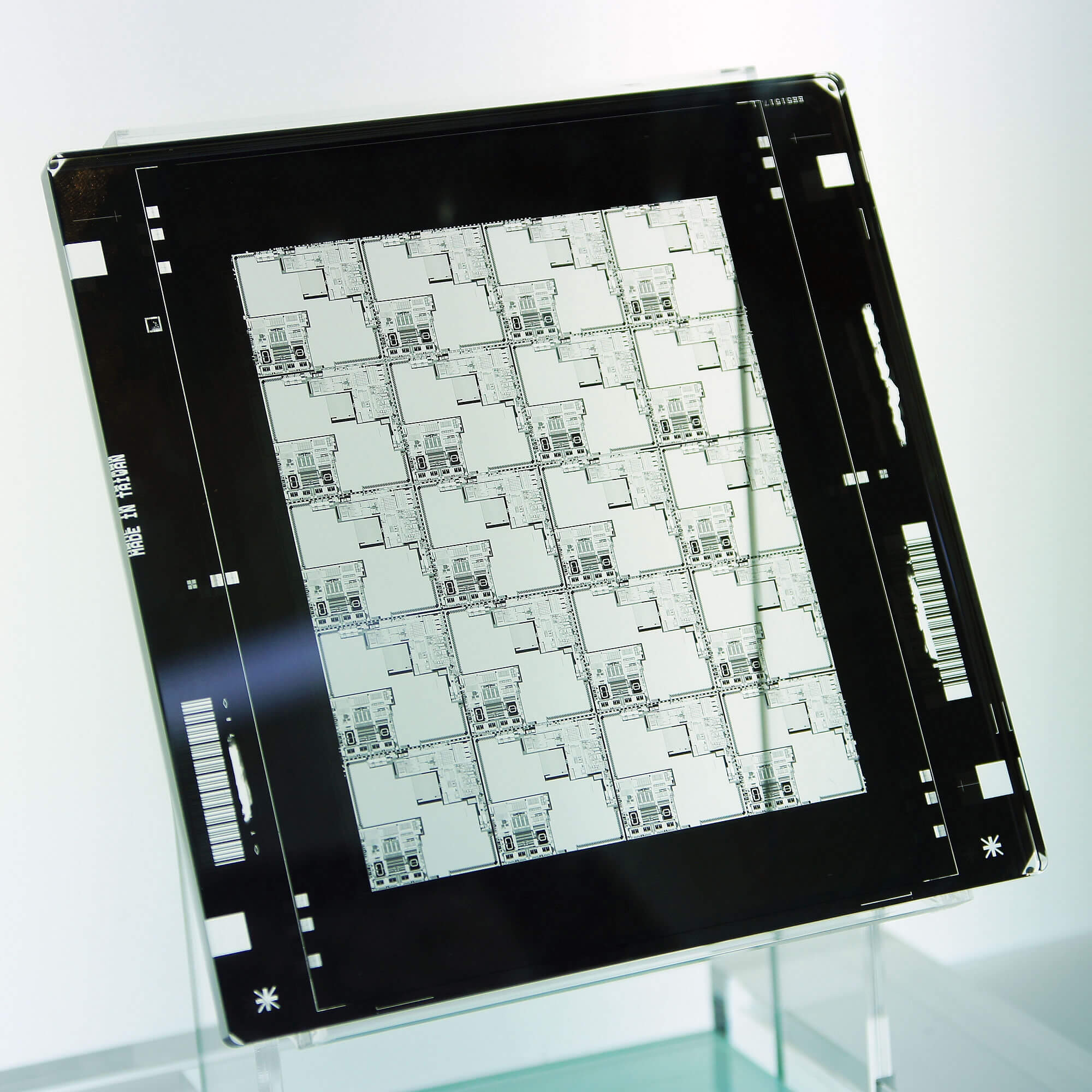

At this point, we need to accept a expect at a process called photolithography: light is passed through something called a photomask, which blocks light in some areas and lets it through in others. Where it passes through, the calorie-free is so heavily focused into a small spot and it then reacts with a special layer used in the manufacturing of the bit, helping to ready out where the various parts are going to be.

Retrieve of it beingness similar an x-ray of your manus: the bones cake the rays, interim every bit the photomask, whereas the flesh lets it through, producing an prototype of the internal structure of the hand.

Image: Peellden, Wikimedia Commons

Light isn't actually used -- fifty-fifty for chips similar the erstwhile Pentium, it'south too big. Yous might be wondering how on Earth light tin have any size, but information technology'south in reference to wavelength. Light is something chosen an electromagnetic moving ridge, a constantly cycling mixture of electric and magnetic fields.

Although we employ a archetype sine moving ridge to visual the shape, electromagnetic waves don't really have a shape. It's more a case that the effect they generate when they interact with something follows that pattern. The wavelength of this cyclic pattern is the concrete distance between two identical points: picture ocean waves rolling onto a beach, the wavelength is how far apart the tops of those waves are. Electromagnetic waves have a huge range in possible wavelengths, so we put them together and telephone call it a spectrum.

Pocket-size, smaller, smallest

In the image below, nosotros tin see that what we call light is merely i tiny part of this spectrum. In that location are other familiar names: radio waves, microwaves, ten-rays and so on.

Nosotros can also come across some numbers for the wavelengths; low-cal is somewhere around 10-7 meters in size or roughly 0.000004 inches!

Scientists and engineers prefer using a slightly different method for describing lengths that pocket-sized and it's nanometers or "nm" for brusque. If we look at expanded section of the spectrum, we can see that light really ranges from 380 nm to 750 nm.

Epitome: Philip Ronan, Gringer

Become back upwardly this article a affect and reread the part most the quondam Celeron flake -- it was manufactured on a 65 nm process node. So how could parts smaller than light be made? Simple: the photolithography process didn't use light, it used ultraviolet light (aka UV).

In the spectrum chart, UV starts at around 380 nm (where light finishes off) and shrinks all the mode down to near ten nm. Manufacturers such as Intel, TSMC, and GlobalFoundries utilize a blazon of electromagnetic moving ridge called EUV (farthermost UV), around 190 nm in size. This tiny wave not simply ways the components themselves can be created smaller, but the overall quality of them can exist potentially better. This allows the various parts to be packed in closer together, helping to calibration down the overall size of the chip.

The unlike companies offering various names for the scale of the process node they utilize. Intel snappily call 1 of their latest ones P1274 or "x nm" for the general public, whereas TSMC merely telephone call theirs "10FF." Processor designers such as AMD create the layout and structures for the smaller process nodes, and then rely on the likes of TSMC to produce them.

TSMC has been diligently working on smaller nodes (7nm, 5nm, and presently 3nm) and making chips for its biggest clients which include Apple tree, MediaTek, Qualcomm, Nvidia and AMD. At this scale of production, some of the smallest features are only 6 nm across (the majority, though, are much bigger than this). To become a sense of actually how small 6 nm really is, the silicon atoms that make up the bulk of the processor are spaced roughly 0.5 nm apart, with the atoms themselves being very roughly 0.one nm in diameter. So, as a ballpark effigy, TSMC's factories deal with aspects of a transistor that comprehend less than 10 silicon atoms in width.

The challenge in aiming for atoms

Leaving aside the mind-boggling fact that chip manufacturers are working towards features being only a handful of atoms across, EUV photolithography has raised a whole bunch of serious engineering and manufacturing problems.

Intel notably struggled to get its 10 nm product up to the aforementioned level as their 14 nm ane and GlobalFoundries had issues of its ain getting vii nm and smaller production systems working. Although Intel and GF'southward bug may not be due to the difficulties inherent to EUV photolithography, they can't be entirely unrelated.

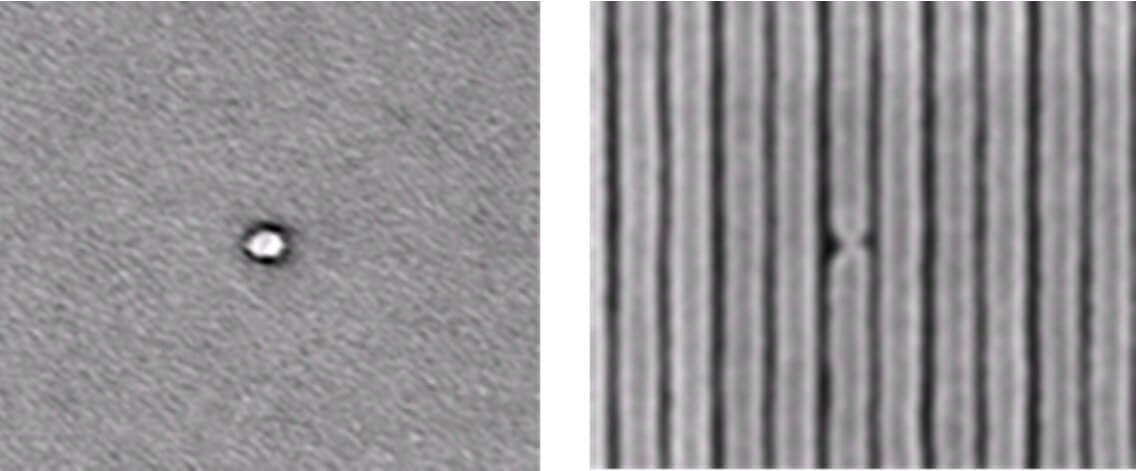

The shorter the wavelength of an electromagnetic wave, the more energy information technology carries, which results in a greater potential for harm to the chip being manufactured; very small scale fabrication is highly sensitive to contagion and defects in the materials beingness used, too. Other problems, such as diffraction limits and statistical noise (natural variation in where the energy transferred by the EUV wave gets deposited into the chip layer), also conspire confronting the goal of achieving 100% perfect fries.

Ii manufacturing defects in a chip. Prototype: Solid State Technology

In that location's also the problem that downwardly in the weird globe of atoms, the menstruum of electricity and the transfer of energy can no longer be causeless to follow classical systems and rules. Keeping electricity, in the form of moving electrons (one of the iii particles that brand upwardly atoms), flowing down conductors closely spaced together is relatively like shooting fish in a barrel at the calibration nosotros're used to -- just wrap the conductors with a thick layer of insulation.

At the level Intel and TSMC are working at, this becomes much harder to achieve because the insulation isn't actually thick plenty. For the moment, though, production issues are almost entirely related to the problems inherent to EUV photolithography, and then it volition be few years yet earlier we can starting arguing in forums that Nvidia handles quantum behaviour better than AMD or other such similar nonsense!

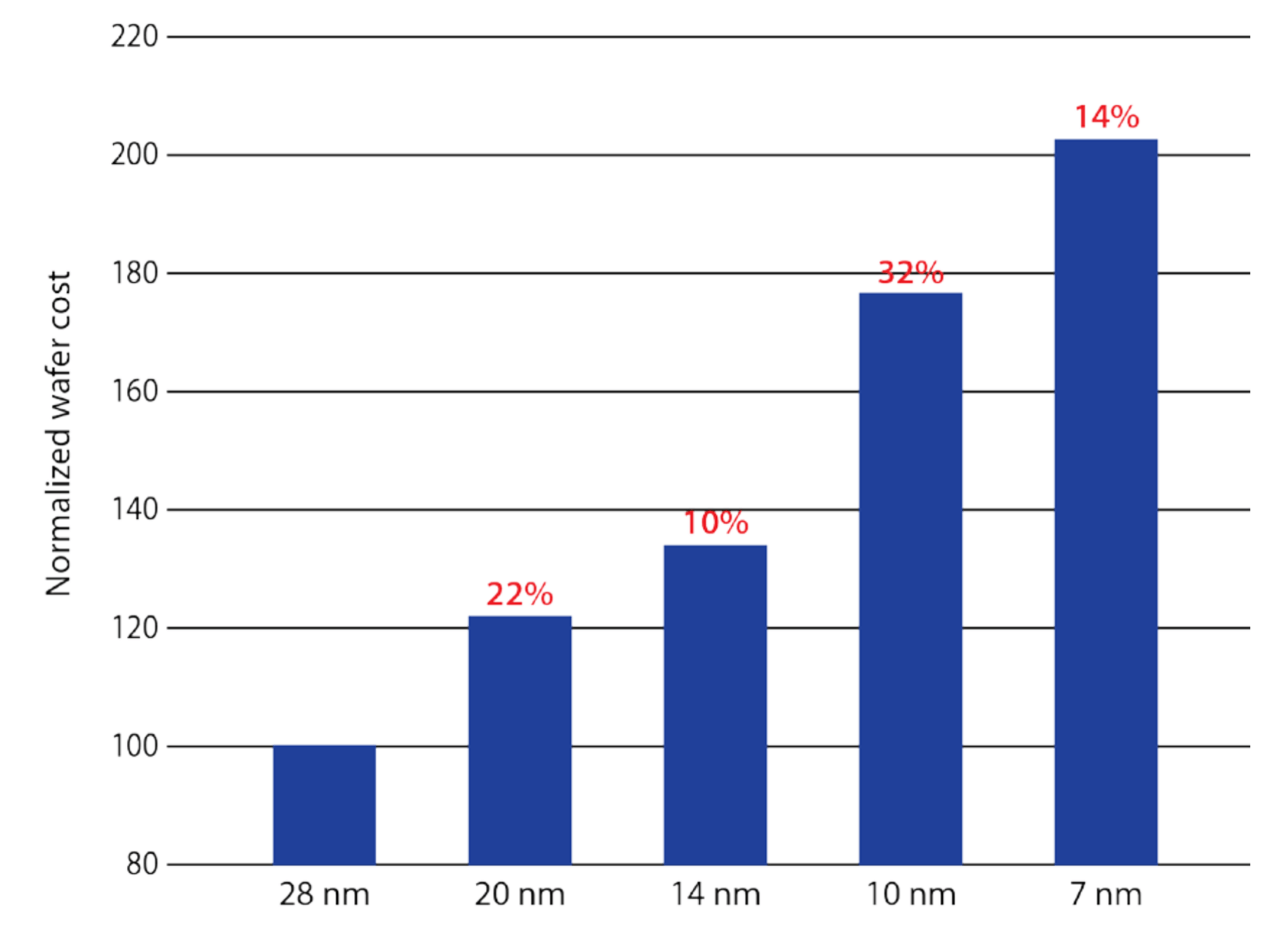

This is considering the real problem, the ultimate reason behind the production difficulties, is that Intel, TSMC and all their fabricating chums are businesses, and they're aiming for atoms for the sole purpose of generating future acquirement. In a research paper past Mentor, the post-obit overview was offered as to how much more wafers cost for smaller procedure nodes...

For case, if we assume the 28 nm process node is the aforementioned i that Intel used to manufacture their Haswell range of CPUs (such as the Core i7-4790K), and then their 10 nm system is costing nigh twice every bit much per wafer. The number of fries that each wafer can produce depends heavily on how big each chip is, but going with a smaller process scale will hateful a wafer can potentially yield more chips to sell, helping to offset the increase in costs. Ultimately, though, as much of this cost every bit possible will exist pushed to down onto the consumer past raising the product retail price merely this has to exist counterbalanced confronting industry demand.

The rise in smartphone sales over the past years, along with a near exponential growth in smart engineering in homes and cars, has meant that chip manufacturers have been forced to blot the fiscal hit from going to smaller procedure nodes until the whole system is mature enough to churn out high yielding wafers (i.e. those that contain as few defects as possible) in high volumes. Given that we're talking most billions of dollars here, it's a risky business concern and a expert part of the reason why GlobalFoundries bailed out of the process node race.

Hereafter prospects

If this all sounds somewhat doom-and-gloom, then we shouldn't forget that the immediate time to come does look positive. Samsung and TSMC have been running their 7 nm production lines to a healthy margin for a while now, in terms of volume and revenue, and chip designers are also planning ahead past using multiple nodes in their products.

AMD'southward chiplet design and strategy that debuted with their 3rd-gen Ryzen CPUs is existence replicated by other chip makers. In this case, AMD'due south desktop PC processor used two chips manufactured on TSMC's seven nm node, and i xiv nm flake made by GlobalFoundries. The onetime were the actual processor parts, whereas the latter handled DDR4 retentiveness and PCI Express devices attached to the CPU.

The above chart shows Intel's procedure node changes over the past 50 years. The vertical axis shows the node size by factors of 10, starting all the way upward at 10 000 nm. The chip behemothic has followed a rough node half-life (the time taken to reduce the node size by one-half each time) of 4.5 years.

Then does that mean we will run into a 5 nm Intel by 2025? Probably yeah, despite their stumble with 10 nm, they are working hard on their way back. Samsung and TSMC have been forging alee with their 5 nm production and beyond, and so the futurity does expect good for processors of all kinds.

They'll be smaller and faster, using less energy and offer more performance. They'll pb the way to fully autonomous cars, smartwatches with the power and battery life of current smartphones, and graphics in games beyond anything seen in multi-meg dollar films from ten years ago. The hereafter is indeed brilliant, because the future is small.

Note: This characteristic was originally published in June 2022. We have revised and bumped information technology because information technology'south as relevant today as information technology was before. Part of our #ThrowbackThursday initiative.

Source: https://www.techspot.com/article/1856-aiming-for-atoms-chip-manufacturing/

Posted by: martinezawase1960.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Aiming for Atoms: The Art of Making Chips Smaller"

Post a Comment